Originally published on Medium.

Doctolib has been growing rapidly over the past 5 years, as has our code base. We have been able to deliver numerous features in a timely manner, but oftentimes at the expense of code legibility and simplicity. The year 2018 was for us an opportunity to step back, learn from our mistakes, and set goals in order for us to regain control over our frontend. Specifically, we re-defined technical debt and legacy code and took measures to reduce it so that we could keep growing at an ever-faster rate and continue to ship features that practitioners and patients love.

Identifying pain points

Twice a year a team of people with a strong interest in JavaScript gather to discuss frontend at Doctolib. One person from each feature team is selected to join the meetings. Nevertheless, the meetings are also open to anyone, as long as they express an interest and have proved themselves to be proficient in JavaScript.

In advance of these meetings, we circulate email surveys to all of the software engineers to identify their specific issues and struggles. Below is an extract from the latest survey we sent out in November 2018:

- What is your biggest pain point on the frontend stack?

- What elements are holding you back? What prevents you from being more effective?

- Is there anything you don’t understand/you don’t master? RxJS, recompact, react-form? React context, HOC, …?

- Is the directory structure good enough? Does it make sense?

- Any tool-related problems? (Prettier, IDE, Chrome DevTools)

- Apart from

console.log, how do you debug? - Do you know Jest? Do you know how to write JavaScript unit tests?

- Do you know what React components we have? Do you know how to use them and what props they expect?

These simple, short questionnaires allow us to gather valuable feedback from all of the engineers. Using them, we are able to identify the most-cited problems and define what legacy means at Doctolib during our bi-annual meetings.

After analyzing the results of these surveys, we usually come up with a new direction and a list of tasks for the following two quarters. These actions are then shared with the rest of the engineers during an all-hands meeting with the entire tech team.

What is legacy code at Doctolib in 2018?

RxJS

When Doctolib was in its early stages, state management for React apps was still very experimental and there was no consensus about which way to go. Two emerging libraries were becoming fashionable: Redux and RxJS. The decision was made to pick RxJS, but it could have just as well been Redux.

Over time, RxJS usage grew and the library was soon imported into every file and used for just about anything and everything: app state management, tiny component states, forms, buttons, AJAX requests, etc.

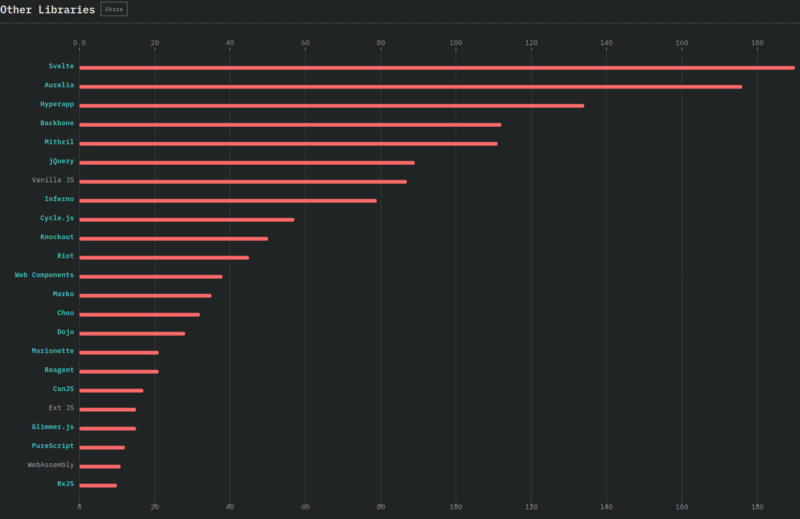

Why is this legacy now? Well, first of all, RxJS is not entirely legacy but the way it’s being used at Doctolib is. This is mostly because it has been used for everything, although its use cases are normally meant to be very specific and restricted. RxJS also makes unit testing difficult because Observables need to be mocked-up. Reactive programming is not known by many, as indicated on the graph below, therefore it does not help shorten new joiners’ ramp-up time — quite the opposite, to be honest. Our aim is to restrain its use cases to what it was originally intended to be used for: event-based computations and asynchronous sequences of data.

Recompose/Recompact

At the same time as RxJS was released, another helper library came out: recompose. As recompose was not meeting all of our needs, the project was forked, patched, and renamed as recompact. Once again, it quickly spread across the code base, bringing Higher Order Components everywhere, as well as additional complexity for new joiners.

Why is this legacy now? Most helpers from recompact can be written in vanilla React (recompact.pure or recompact.withProps to name a few). Given that early advocates of recompact at Doctolib left the company a while ago, it became challenging to pass down knowledge and help new joiners get up to speed quickly. Moreover, the original library (recompose) was recently officially deprecated because of an upcoming React feature, Hooks, not forgetting that recompose/recompact rely on the legacy React Context API. We now aim at getting rid of recompact altogether.

jQuery and CoffeeScript

Since the very beginning, jQuery and CoffeeScript have been lying around in the code base. jQuery helped features come to life in no time, bridging the gap between various browsers, oftentimes with poor support for new Web APIs. As for CoffeeScript, it is tightly coupled with Ruby on Rails, our backend, thus it has been there from the beginning.

Why is this legacy now? Starting this year, we only support modern browsers and Internet Explorer 11. Consequently, it does not make any sense to use jQuery when we can write plain JavaScript; and CoffeeScript adds unneeded complexity given that very few people can understand it at a glance, let alone write it.

React unsafe life-cycle methods

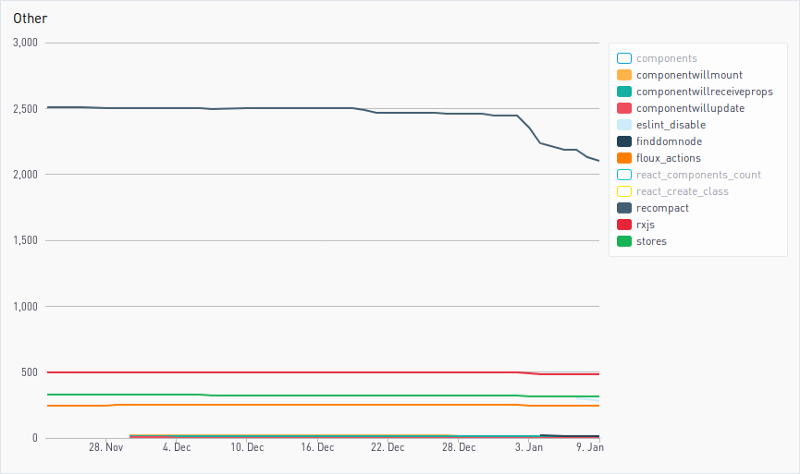

Last but not least, we recently deprecated a few React life-cycle methods and helpers, following the maintainers’ advice about unsafe methods. React.StrictMode was recently introduced as a tool to help detect potential issues within an app. We cautiously started adding it in the codebase, to avoid having too many warnings popping up here and there while developing. Here is the list of life-cycle methods or helpers we decided to deprecate early in our codebase: componentWillMount, componentWillReceiveProps, componentWillUpdate and findDOMNode.

Tackling and killing legacy

After agreeing upon what can be defined as legacy, the time comes to actually kill it. The way frontend legacy is handled at Doctolib is always the same; we pretty much stick to MOM: Measure, Optimize and Monitor.

Measuring is done by way of our survey and our own experience while developing. While evaluating the relevance of each pain point collected, we prioritize them according to the number of times they are mentioned. We also assess the feasibility over the short-term: short and easy tasks tend to move up on the list of actions. Finally, these actions become Tech Tasks.

Optimizing is done progressively, after our bi-annual meetings, through special tasks we call Tech Tasks. These tasks are differentiated from regular feature tasks by their very own nature: they are purely technical tasks whose goal is to improve platform stability, security, and performance as well as to reduce technical debt. People usually pick the ones they like best when they work on Tech Tasks (Fridays are Tech Tasks days for most feature teams). However, a few big and/or complex tasks do get assigned during our bi-annual meeting in order to make sure that they will eventually be carried out. These big tasks are prioritized by the solution architects and engineering managers on a regular basis to ensure they fit into the roadmap.

Finally, monitoring is done throughout. It is a never-ending process. At the end of every meeting, we set KPIs to “track” and then we immediately create dashboards to track usage of “legacy” through these KPIs. One person is in charge of creating these graphs, usually the same person who called a meeting in the first place. Basically, this translates to metrics we expect to drop.

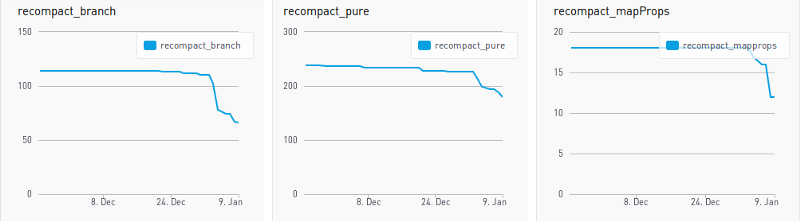

These three graphs above show the number of lines in our code base containing a deprecated function. This is how we compute these numbers:

We also create less-specific dashboards which list the “general” legacy functions and libraries we aim at reducing or killing altogether.

These graphs are a helpful starting point from which we can monitor progress.

Preventing people from using it

There is a long-lasting tradition of heavily relying on static checks at Doctolib. Essentially, they are script files which we run on source code as it is — before transpilation and bundling. Our CI pipeline runs these tests first, before running any of our 8000+ end-to-end tests. Below is the one test which checks for new lines containing deprecated React methods and recompact helpers, and then reports on Pull Requests.

In addition to relying on static checks, we also regularly inform and remind people about our best practices on the frontend stack. We usually demo state-of-the-art JavaScript once a month, during what we call “Tech Time” — a meeting for and by software engineers. It’s also a good opportunity to show how much progress is being made on reducing legacy code.

Meeting objectives

Oftentimes, the long tasks tend to remain “in progress” forever and people lose interest in them. This is when the people who first defined these objectives come into play. It is their responsibility to help these tasks reach a conclusion by supporting those working on it and providing a helping hand if need be.

In any case, every bi-annual meeting starts off with a review of what has been achieved during the previous term and carries on from there.

Long-term vision

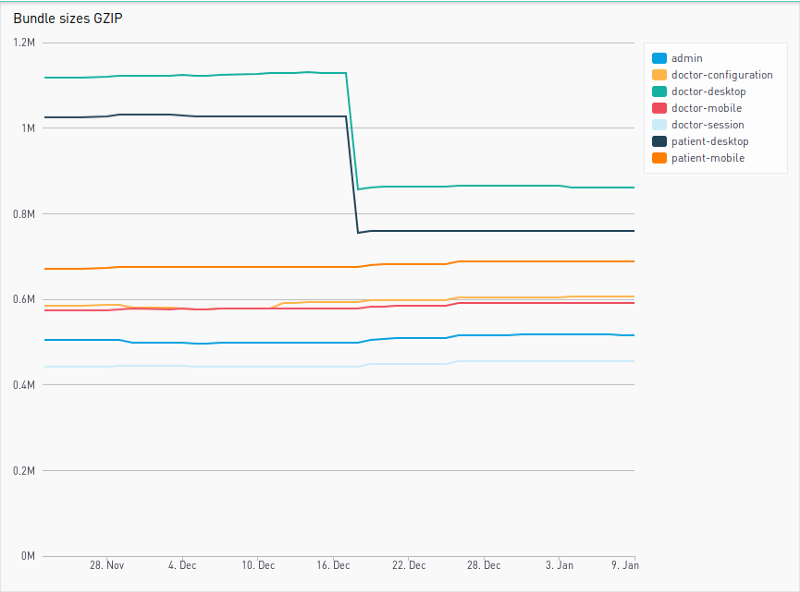

Deprecating these few React functions, recompact, a significant part of our RxJS usage, jQuery, and CoffeeScript is a major first step. By doing so we can ease new joiners’ onboarding, keep up with the latest JavaScript standards, and reduce our technical debt. It also belongs to a bigger picture. Creating these dashboards opens the door to more monitoring, which ultimately means more control. A recent concrete example is the bundle size dashboard, which we introduced a few weeks ago.

Not only does it store the sizes over time but it also reports on Github Pull Requests. A handy npm package called bundlesize checks that every build does not exceed thresholds defined in our package.json file.

In addition to more monitoring, we’ll keep collecting feedback on a regular basis from all of the software engineers, calling for more meetings when needed. We will specifically be paying attention to new joiners, how they feel about the frontend stack and how we can make their onboarding even easier. We don’t want to be held back by legacy code. Instead, we want to be able to experiment with new technologies when relevant, adopt the latest JavaScript standards, and keep up with React.

There is still much to do on the frontend. A Single-Page-Application is much more than just a website. It’s software that runs in a browser. Hundreds of different browser versions actually, operating at various speeds, with unreliable network connectivity. It has to be as good as any software program. The time when servers were the unique focus point has come and gone; frontend requires a different kind of attention, not less.

Originally published on Medium.