After having experienced software development in many languages, from desktop programs to mobile applications and web sites, comes a moment when I felt compelled to standardize my software development process. In the last couple of months, we, at The Smiths, tried to define our workflow more formally by integrating continuous integration. How to properly "synchronize" a team made of many developers, "spread all around the world", in different time zones? How to make sure there is no bottleneck at any level, during the development? First, let’s have a look at the definition.

What is continuous integration? According to Wikipedia, it's:

[...] the practice, in software engineering, of merging all developer working copies to a shared mainline several times a day.

But not only. It's much more than this. Let's dive into continuous integration.

Purpose

Continuous integration is an entire concept that tries to ease software development by making things much easier and more flexible. Like agile methodology, it's been getting more and more popular since the beginning of the 2000's. Nowadays, it tends to be widely adopted in any kind of software company.

Effortless automation

Continuous integration is mostly about automation. By this, I mean being able to deploy flawlessly, many times a day. Like Quentin Adam is used to saying,

The same applies for documentation generation, testing and deploying. Repetitive tasks are most of the time painful and should be performed by computers.

Continuous testing

Every new release should be tested. Automatically. Without any human intervention. In a safe and minimal environment, not a human's environment with tons of programs, custom environment variables, outdated dependencies, etc. It's a human job to design the tests but running and validating them is a machine job. This way, the results can be shared with an entire team over automatic emails and archived.

Documentation

Writting documentation is for humans. Generating it is for machines. Again, it's a repetitive task that no one should be assigned. It's a waste of time. Machines can do it instead of us, at the right time, usually when a new release is about to come out. Furthermore, machines don't forget to bump the version numbers.

Deploying

With continuous integration, deploying should be as simple as a git push. When time has come for deployment, no one has to use ssh or rcp, not even ftp. It's unsafe insofar as it's too much of a risk to let a human get inside a production machine. A developer has nothing to do in a production machine, as long as all the tests have been passed before pushing to production. All one can do is breaking something. A production machine is meant to be administrated by a sysadmin, no one else. Once it's set up, the only action required by developers is pushing code when it's ready to go live.

It's the same story for releases. Packaging and releasing a new version must be a simple task anyone can do, not only the CTO, regardless of the OS, configuration, and so on.

Why

Now that I exposed the principles of continuous integration, the question you may want to ask is "Yes, but why?". Indeed, prior to continuous integration, everything was already working well, more or less. So, you might wonder how anyone can benefit from continuous integration.

In fact, continuous integration should simply be regarded as an entire development workflow. It enables your team of developers (or even a single developer) to be more agile. You can easily get rid of god-awful tasks without actually deleting them, just by delegating them to computers.

In parallel, you can improve maintainability and evolutivity of the software produced by adopting the right versioning and bug tracking tools. How? Let's take an example.

Remember in the old days, when you used to package your code into a zip file and name it according to the version? How boring it was to keep all of those files. Was it easy to track differences between two given versions? How could you determine the changes? How could you apply hotfixes on an old (but still in use) version as well as on the latest one? How could you know which developer had written which feature? Here come the version control systems, or more simply, Git.

Another example. For every new version (and sometimes between two) you had to set up your environment correctly, generate the documentation from source code, bump the version number in both code and documentation, run unit/integration/system tests and finally, if everything goes well, compile it for as many platforms as you support (which quite often would mean a lot), and make it available on a website (or somewhere else). Well, how pleasant would it be if all of this could be achieved right after a git push?

Let's now see how to get started with continuous integration, easily.

How

Now, you might have understood that you have to use Git. And if you stil don't know why, you read read my article about Git.

In my opinion, the most important thing with continuous integration is... your Git workflow. You have to remain consistent from the beginning of a project to its end. Everyone involved has to be careful and focused at each step. Working within a big team is not something easy. Everyone has different schedules, information doesn't spread that well. That's why having a robust and error-proof Git workflow matters.

At The Smiths, we identified four main components that we wanted as core parts of our Continuous Integration process:

- Semantic versioning

- A Git workflow

- Travis-ci.org

- Agile methodology

Semantic versioning

We decided to stick to the very simple rules proposed by semver.org. Basically, it says that a version number should be something like MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, where (what follows has been extracted from their website):

- MAJOR version when you make incompatible API changes

- MINOR version when you add functionality in a backwards-compatible manner

- PATCH version when you make backwards-compatible bug fixes

Sticking to this rule forced us to think more about the logic behind the versions, reshape road maps more precisely, and allowed us to bump our version numbers more cleverly. We applied this to our mobile apps and Titanium widgets, bumping version numbers carefully over time.

A Successful Git Workflow

This part is clearly the most important, as it’s being used every single day by everyone. In general, it’s likely the most important aspect about continuous integration, to which we had paid a lot of attention.

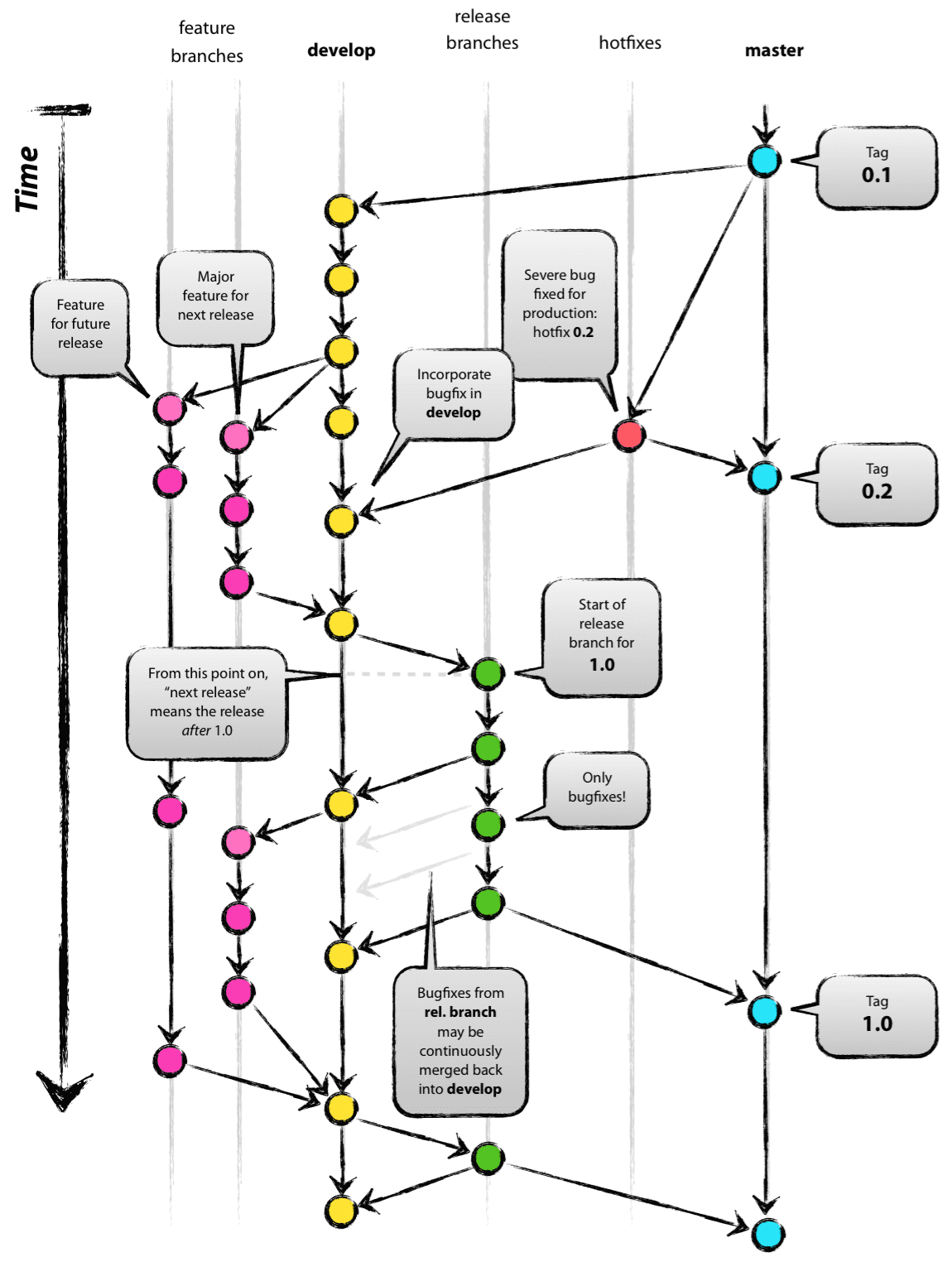

After some research, we came across a very popular Git workflow, the branching model.

This picture has been taken from A successful Git branching model, by Vincent Driessen (thanks to him). Overall, it’s the best Git workflow we’ve ever encountered. So we adopted it, with some specificities: we made a few minor changes to that original branching workflow, in order to better suit our needs. It can be applied to any kind of software project. I also need to mention that we use GitHub, the most famous web-based Git repository hosting service, because it offers some great features, such as Pull requests, a bug tracker (issues), etc. Moreover, as most of our code has been open sourced (except our clients’ core apps), it’s not a problem at all. By the way, it also gives us a greater visibility, it’s like giving away our widgets to the Titanium community thanks to GitHub.

Now, let's move onto our workflow that we daily use, with Github:

Our Git workflow

- There is a remote repository called

origin. Then, every new developer (including the owner) has to fork this repository. Theoriginrepo will ONLY contains two branches:masteranddevelop. master: contains only the stable realeases (General Availability), tagged with

git tag -a

Those are production releases.develop: contains only stable code with newly developed features. This branch has been created with

git checkout -b develop master

It’s the latest cutting-edge release (Release Candidate). It may contains some bugs.- No one is allowed to commit into

masternor intodevelop(except for the first commit intomaster, thendevelopis forked frommaster), in eitheroriginor the forked repository. Not even locally! - There's one developer responsible for the entire project. Let's call him/her Integrator.

- To add a new feature, one of the developers create a local branch called

feature-xfromdevelopand commit into it. He/she may push this branch to their own forked repository. - When this feature is fully developed and tested, and ready to go into

develop, the developer creates a Pull request from the forked repository toorigin(from branchfeature-xtodevelop). Then, only one person can accept it and merge it: Integrator. He/she can also refuses it and comment about the reason(s). - If the Pull request has been accepted, everyone has to update their

developbranch (locally and on their forked repo). - The same applies for hotfixes: anyone can create branches called

hotfix-yand create Pull requests from them. - When time has come for a new release, Integrator merges back

developintomasterand tags it with a release number (according to the Semantic versioning). Then, anyone update theirmasterbranch. - Everyone is strongly encouraged to rebase on top of

masteras often as possible, especially before submitting PRs.

In case you're working alone on a project, no need to fork anything. Just apply the same principles to the only remote repository (Pull requests, merge, etc). You can skip Pull requests if you want so, it just helps keeping a trace of every new feature.

I've found out that this workflow works pretty well with any of our projects, might it be an entire app or a mere widget. However, as I said we've made some adjustments to the original workflow found on the Internet, making it a bit simpler to use.

Issues are also great features brought by GitHub that allow us to track down bugs and list them. One can assign people to fix an issue, and let others know of its progression thanks to emails or notifications. Issues can also be linked to specific commits which helps a lot when tracking regression bugs.

Finally, we're also taking advantage of Milestones, a GitHub feature, which can be seen as a simplified scheduler, permitting us to create deadlines with goals to reach. It's somehow a list of deadlines with progress bars automatically filled as we would create and merge Pull requests.

Some commands

To generate the message for a Pull request:

git log --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit <branch-from>..<current-branch>

# Prints the commits you made since last merge and the associated messages

To update develop (works with master as well):

git fetch origin

git checkout develop

git merge --ff-only origin/develop

# Only fast forward is important to keep the history clear and clean

To update a feature branch (after a PR has been merged):

git fetch origin

git checkout feature-x

# Three options (choose only one):

# 1.

git merge --ff-only origin/develop

# 2. If this fails because you have commits ahead, do:

git rebase origin/develop

# 3. If you're a badass and want to ignore your own changes:

git reset --hard origin/develop

To merge a Pull request (only Ingrator is supposed to do it) and push it:

git remote add feature-x_repo git@github.com:someone/forked-repo.git

git fetch feature-x_repo feature-x

git checkout develop

git merge --no-ff feature-x_repo/feature-x # You could add --no-commit to edit files before committing

# 'no fast forward' is important to keep the history clear and clean

git push origin develop

To delete a branch (locally and remotely) once it has been merged into the main repository:

git push feature-x_repo --delete feature-x

git branch -d feature-x

Contributors

There's another approach to the scheme above. Instead of using only Pull requests, you could add other developers as contributors. This way, there's no Mr/Ms Integrator, any contributor is free to merge their features into develop. Also, feature branches can be on the remote repository.

Git branching model considered harmful

The Git workflow we used as a starting point (the branching model) has been considered harmful by someone, and thus that person proposed another model. The reading is worthwhile although I'm still not fully convinced by this alternative.

Travis, the all-in-one tool

Soon, Travis will be your best friend. But first, what is Travis?

Basically, it's an online service delivered through a website, providing sets of virtual machines started especially for a developer whenever needed. Those machines run some scripts and shut down themselves automatically. Usually, a developer sets up their Travis account to run scripts on every git push performed on a GitHub repository. However, one can configure Travis to be run with any kind of Git hook. Travis is free but they also have paid services with much more features (that we didn't require).

So, how is Travis so helpful for us?

Most common use cases of Travis

Well, one can imagine dozens of scenarios. Documentation generated from the source on every new git push in develop? Easy. Running a whole set of tests automatically? Easy as well.

Let's dream a bit further... One of the most fancy things one can do is running a set of tests, bump version numbers in the code and the documentation, compiling the software program and generating the updated documentation, pushing the binaries to Amazon S3 and the documentation to GitHub Pages, and making the whole set available to everyone, automatically! And yes, Travis, can push into specific branches as well. That might be really useful to update web pages automatically (a link to the latest stable release, listed on a download page, for instance).

That is definitely the most perfect and automated scenario one could imagine, but that's easily achievable, although it would take quite a long time to set it up.

An example with Github Pages

A good example is my blog (yes, the one you're reading). My articles are written in Markdown and contained in the branch master. However, what you're reading, is a Github page (contained in a branch called gh-pages). What is happening hunder the hood is that, every time I push on master, Travis fetches it, generates the HTML pages from the Markdown files, and pushes them to the branch gh-pages on Github. This way, my blog gets updated automatically.

I followed this tutorial to do that (and this presentation as well).

How does it work

At the root of your repo, just add a .travis.yml with some pieces of configuration inside. And you're done! A few more options are available on their web interface as well.

You can have a look at my .travis.yml for this blog.

Tips with Travis

- Get a new token from Github in order to give Travis access to your repo

- In travis, disable Build on Pull requests, enable only if .travis.yml is present

Agile methodology

Last but not least, agile methodology. Behind that term that sounds rather complex is a concept pretty simple. In Computer Science, we use the term "Agile Software Development". Wikipedia says:

Agile Software Development is a set of software development methods in which requirements and solutions evolve through collaboration between self-organizing, cross-functional teams. It promotes adaptive planning, evolutionary development, early delivery, continuous improvement, and encourages rapid and flexible response to change.

There is also an official Agile Manifesto that tries to describe it more precisely, based on twelve principles. From that original manifesto have appeared dozens of practices that we refer to as "Agile methods". I won't explain them here as it is not the purpose, for more information visit the Wikipedia page.

The one we picked is called Scrum. Again, I won't explain it here but will instead expose the workflow we adopted, derived from it. For a better comprehension, I recommend you read the Wikipedia page.

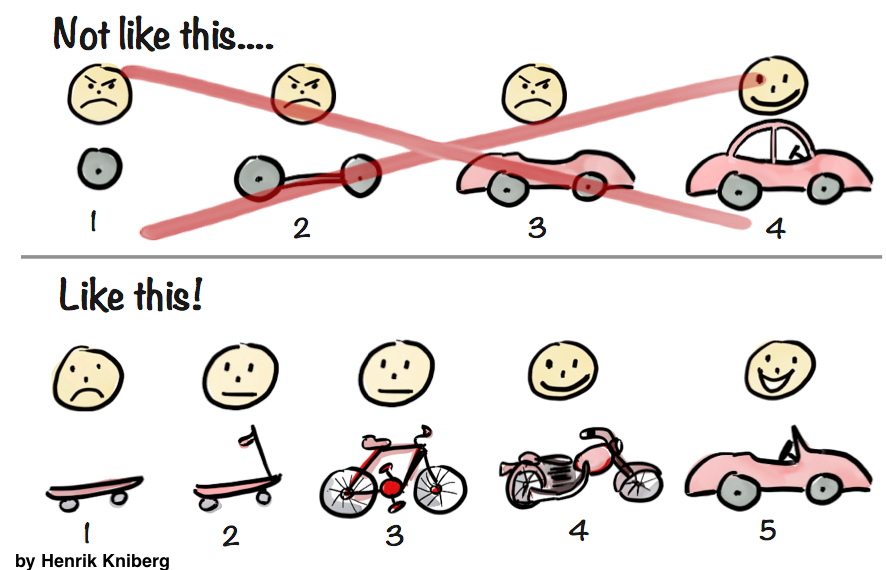

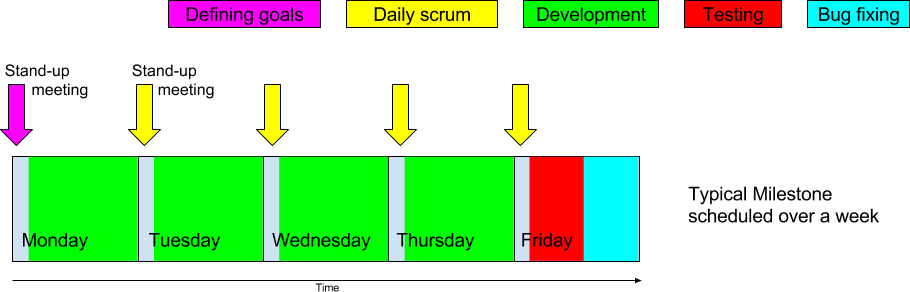

Basically, at the very beginning of the project, the CTO would meet client and discuss with them. As a result, he would obtain detailed specifications from them. Then, all together, we would brainstorm and define Milestones, which are fundamentally the most important steps to a final product. For instance, from scratch, we would aim at developing a MVP (which is a working product, see the picture below), then progressively add features, grouping features under Milestones. As a reminder, "Milestones" is a feature of GitHub. Each Milestone would last a week, tops. In Scrum, Milestones are called Sprints.

Starting with an MVP is the right way to go. The client is always satisfied as they would get a working copy of the product being-developed, at each stage, continuously getting improved. They would not have to wait for weeks or months before being able to test anything.

Then, each developer would get assigned or choose a few features from the first Milestone until completion. Every morning, we would gather for a 10-minute stand-up meeting, during which everyone would say what they did the previous day and what is left to do, especially regarding the current day. Standing forces us to speak concisely and don't waste each other's time, since it is not as comfortable as being sat down.

At the end of the Milestone's week, we would merge all the Pull requests resulting from the features, then review all together all the work done, conduct tests and create issues on GitHub to be resolved before starting the next Milestone. Eventually, we would readjust the remaining Milestones when needed.

This would go on until completion of the final Milestone, which is supposed to bring all the features originally requested by the client.

Sometimes, the part "Bug fixing" would require extra-time. In such a case, we would extend that part onto the next week, only assigning one person, so that the rest of the team could stick strictly to the rule "a Milestone per week". But that rarely happened fortunately.

Mix them all

As a brief conclusion, when thinking back at all the parts of our workflow, one can see that it's an entire whole in which GitHub plays a key-role. Being organized, knowing everyone's role and keeping in mind goals to reach are important as well, just like the tools we decided to go with. Furthermore, being able to release intermediate versions, quickly, allowed us to give constant feedback to the client, which is reassuring.

This workflow is surely perfectible, but until now it has proved really efficient.

I hope this article was helpful. It's a good start with Continuous Integration. First, focus on your workflow (especially with Git) and then set up the right tools (including Travis) and you're good!

Resources to go deeper

- Introduction au déploiement continu

- Qu'est-ce que l'intégration continue ?

- You're Doing Agile Wrong

- SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT EXPLAINED WITH CARS

- Continuous Integration

- Déploiement continu avec Travis-CI (et GitHub Pages)

- Scrutinizer

- GitHub Flow

- Intégration et déploiement en continu @ Github (Alain Hélaïli)